MALAKAL, South Sudan (CNS) — Behind the blue-helmeted U.N. soldiers ringing the periphery, their tanks and heavy weapons pointed outward, Maryknoll Father Mike Bassano’s parish is a tightly packed maze of tents and tarpaulins filled with people hiding from war.

Father Bassano is the only priest amid the 25,000 civilians who live inside the civilian protection area of the U.N. base here.

“This is where the church should be,” the 66-year old priest from Binghamton, New York, told Catholic News Service.

“In Maryknoll, we believe we should be with people at the margins, and you don’t get any more marginal than this. I’m in love with the people here. They’ve welcomed me and I feel part of their lives,” he said.

The camp remained tense in recent weeks as fighting between rival army factions approached the edge of the base. A mortar fell just outside the camp, and a U.N. vehicle was hit by gunfire. The airstrip inside the base had to be closed for several days, preventing anyone from evacuating to the relative safety of the capital.

Almost 120,000 people remain sheltered in U.N. bases across South Sudan. The bases were established to house the large U.N. peacekeeping contingent that has been a permanent fixture since before the country’s independence in 2011.

Most of the people living inside the Malakal base came seeking refuge when fighting broke out in late 2013. A political feud in Juba between the country’s president and former vice president, who come from different tribes, quickly spread throughout the country, rupturing the army along ethnic lines.

Father Bassano had been in Malakal two months when the war broke out. He came to South Sudan from Tanzania to be part of Solidarity with South Sudan, an international community of Catholic groups supporting the training of teachers, health care workers and pastoral agents in the world’s newest country. Living in Solidarity’s Malakal teacher training college with other members of the group, he was learning Arabic, visiting hospitals and working with pastoral workers in a local parish.

And then the shooting started Dec. 24, 2013, and he was forced to crouch on the floor of a bathroom — it was the best protected room in the house — with three Catholic sisters.

“They had all seen war before, but this was my first time,” said Father Bassano. “All I could say was, ‘Lord, I don’t want to die now, but may your will be done.’ We prayed that Jesus, the prince of peace, would protect us and the people.”

After four days, the shooting let up and the group eventually made its way past burned vehicles and bullet-riddled bodies to the U.N. base. Father Bassano ended up being evacuated to Rumbek, where he helped at a girls’ school run by an Irish congregation. But his heart was back in Malakal.

The fighting continued for months, however. Malakal changed hands six times. Most of the pastoral workers in the diocese remained in other areas of the country.

The U.S. priest eventually returned last September, yet he found most of the city’s 250,000 people were not there. Solidarity’s college had been looted, and the city was still unsafe, so Father Bassano moved into the U.N. camp to accompany the people living there.

He works with a Catholic community that he said is well-run by laypeople in the camp. He spends his mornings walking through the camp, stopping to listen to people, taking note of concrete needs that he passes on to catechists and the Legion of Mary when he meets with them late in the afternoon over tea.

The camp has not been exempt from the ethnic tensions that cause bloodshed outside. When youth gangs formed inside the camp, the parish organized a music and dance group, intentionally involving youth from different tribes.

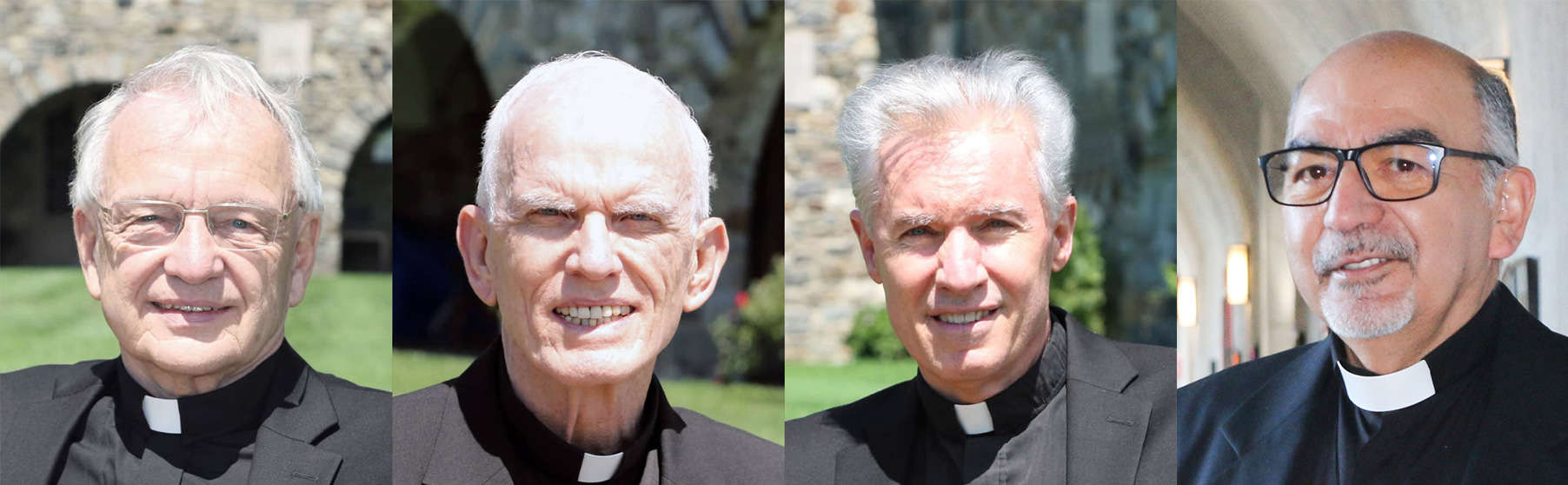

Maryknoll Father Mike Bassano greets people during the sign of peace at Mass April 9 in a makeshift chapel inside a U.N. base in Malakal, South Sudan.

Maryknoll Father Mike Bassano greets people during the sign of peace at Mass April 9 in a makeshift chapel inside a U.N. base in Malakal, South Sudan.

In December, the congregation built a makeshift sanctuary out of wooden poles and tarp material. Because it’s located in a largely Nuer section of the camp, Father Bassano said, its dedication was an opportunity to discuss difficult issues.

“The church isn’t a place; it’s a way of being together. So even though we’re in a Nuer area of the camp, we intentionally invited Shilluk and Dinka from other areas of the camp, especially the youth, to come here. It’s a place where diverse people come to become one people, worshipping God together. Every time we gather on Sunday for worship, we are a family of God, not divided by tribe, at peace with each other,” he said.

The priest said unity took on special significance during this year’s Good Friday liturgy, which came at the end of a Holy Week in which Malakal erupted in renewed fighting, not between the government and rebels, but between different ethnic factions within the army. Over a three-day period, more than 4,600 new civilians sought refuge in the camp.

On Good Friday afternoon, Father Bassano said, three people were reading the Passion narrative in Arabic from the Gospel of St. John when his cellphone rang. He said he usually turns it off for worship, but some intuitive sense made him leave it on that day.

“I’m sitting behind the altar and the phone starts ringing. People are noticing so I have to answer it. It takes me a moment to get it out from under my robe, and I answer in a low voice, sort of crouched down behind the altar so no one would see, even though that’s hard to do,” he said.

It was a relief official, telling the priest that she needed space to house 230 people. Could they use the church? Father Bassano asked when, and she said right away.

“When the Passion reading ended, I told the people that we were celebrating the historical death of Jesus. ‘But today it is happening again in the suffering of people who are right now on their way to be with us,’ I said. ‘Will we take them in?’ The people said yes and applauded. My phone rang again and the woman told me they were on their way,” Father Bassano said.

The priest sped up the liturgy.

“At the end of communion, I looked out the door of the church and there they were, walking toward us, some with buckets and mats on their heads. So I said … let us go now in the peace of Christ to welcome our sisters and brothers. And we did. We took the chairs out of the church and the people came in, and soon the space was full.”

“We didn’t only pray the ritual of Good Friday. We lived it by welcoming the suffering Christ among us,” he said.