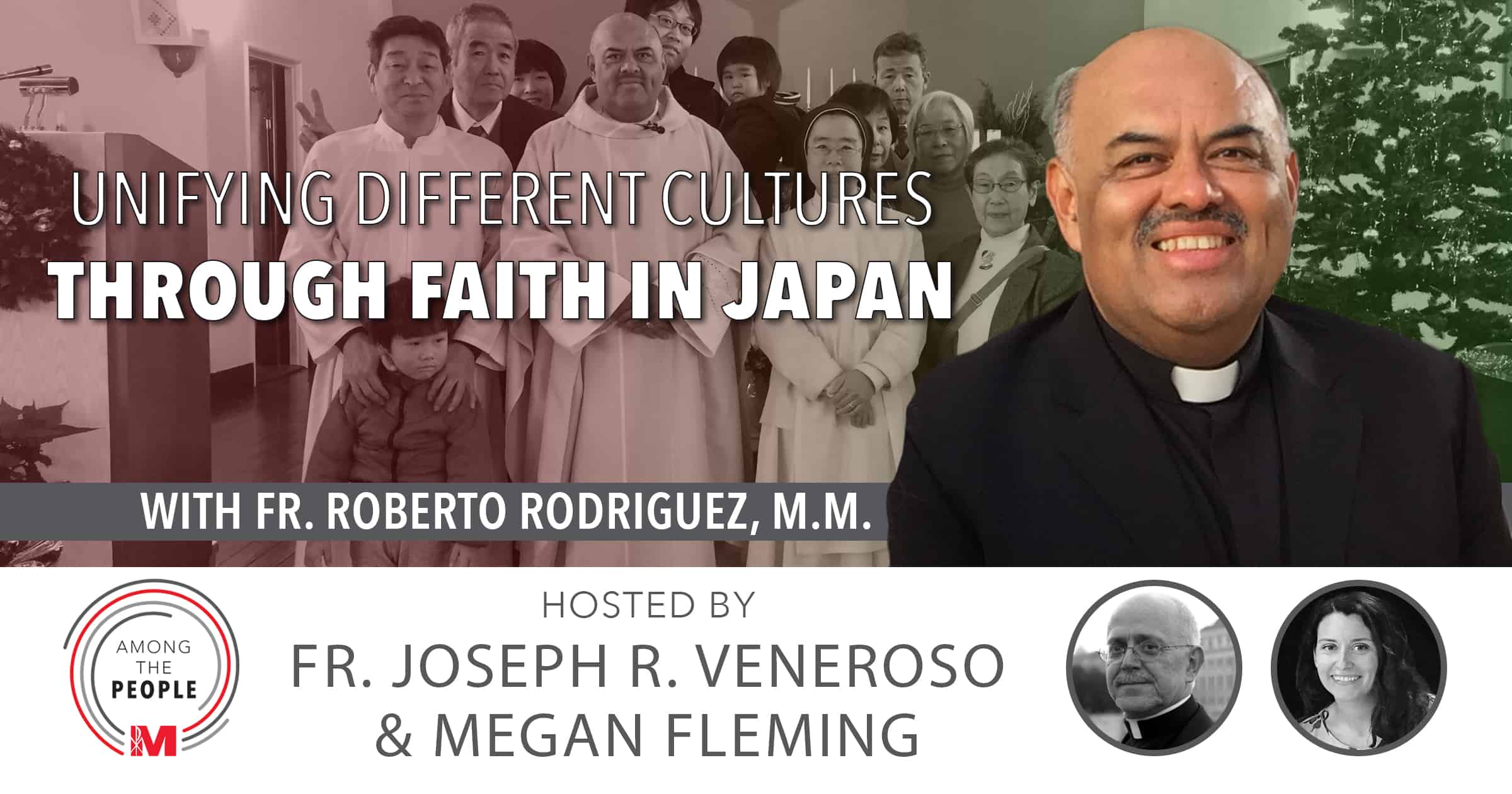

An interview with Maryknoll Missioner, Fr. Roberto Rodriguez

Fr. Joe: Father Roberto, good to see you again. How have you been?

Fr. Roberto: Very well, Father Joe. Thank you for having me.

Fr. Joe: I’m trying to think of last … Thank you. I was trying to think of last time I saw you, but it’s been awhile, and all this time you’ve been in Japan.

Fr. Roberto: I have been, more than 10 years now.

Fr. Joe: 10 years in Japan. So tell us, what are you doing there?

Fr. Roberto: Well, in Japan currently, I am the parish priest of two Japanese parishes. One is located in the city of Nabari, the other one is in the city of Iga Ueno. Both of them in the Kyoto diocese.

Fr. Joe: Okay, and are the parishioners all Japanese or is there a mixture?

Fr. Roberto: Nowadays, we have a great coming in of Catholic from other countries, but the base of the parishes, which were established by [inaudible] 60 years and more ago are basically Japanese. The Nabari parish has a few Indonesians, Vietnamese members. However, the Ueno parish, which is called the Holy Child of Jesus Parish, has in the thousands, and I mean in the thousand.

Fr. Joe: Really?

Fr. Roberto: Migrants, primarily from Brazil. We speak about 10,000 within the area of the city. We have maybe 3,000 Peruvians. Likewise, Filipinos, and the latest wave or migrants are coming from Vietnam, many of which are also Catholic. So the parish at Ueno is having a multicultural, multilingual parish community.

Fr. Joe: [Muy católico 00:01:28].

Fr. Roberto: Muy católico.

Fr. Joe: Here, it’s very Catholic and it represents everyone.

Fr. Roberto: It’s interesting.

Fr. Joe: So that must mean you get involved in a lot of work with the migrants.

Fr. Roberto: Correct. When I got there, this reality was already present. I just happened to be assigned there, because the Bishop learned that given my Central American background, being born in El Salvador, I speak Spanish, come into the United States, becoming an American, I learned English … Eventually I was sent to the Philippines by Maryknoll before this assignment, and I learned the language of the south of the Philippines, and also Japanese, which I studied as soon as I got there. I studied it for three years, full time. And so with that in mind, he said that he needed to move me to this particular new assignment, so that I will pay attention to the new reality of the Catholics in Japan, because that’s what is happening.

The Japanese Catholic population is declining, due to the aging population, and the low birth rate, but the Catholic population of migrants is making it to go up. So we have now a different reality than let’s say right after the war, where everyone was Japanese Catholic. Now we have 56% of the Catholic population is foreign-born migrants, who came to Japan, and 44% born Japanese. So that’s the new reality of the Catholic church. It’s not everywhere, but primarily in the metropolitan areas of Tokyo, Saitama, Nagoya, Osaka. And so the people that are responding to the needs of the migrants are basically the missionaries from diverse communities, because they come not only with the need to be tending to, let’s say their spirituality, the celebration of the Eucharist, the sacrament, but also with other necessities such as in occasion legal assistance, because they broke the law, or they lost their job, or they were injured and they are not being compensated, or sometimes they just get into trouble.

Sometimes you know, people do make mistakes, errors, and they get into trouble with the law. Japan is a very strict law-minded society, and also when they lose their jobs, or they are thrown out of their apartments, we advocate for them, give them economical assistance, when that is the case. When somebody dies, usually they don’t have the means to either bury the person, or to cremate the person, or send them home, which is what they like to do. So many times we assist them economically to those, and there are many more necessities, like migrants have when they’ve moved to a new place and they don’t have connections, or money, things like that.

Megan: I’m sure even like the language is a huge … You’re probably assisting them tremendously with just the language barrier alone.

Fr. Roberto: I will claim that. The reason I’m popular right now, because I am, even the Bishop mentioned this to my superior, so I don’t know from the Bishop, but through my superior … He was praising me because when the parishioners come, let’s say from Peru, from Bolivia, from Brazil, they request their baptisms, their house blessings, their car blessings, or a special mass in their own language, and so we accommodate that. And so they really enjoy it. Likewise, when they have primarily big celebrations such as Our Lady of Aparecida for the Brazilian, which is their number one faith, after the foreign language Festival. So I do processions with them. I do festivals with them. Well, that brings a lot of energy, joy, happiness. And so in that regard, I’m very successful, so to speak.

Fr. Joe: Yeah, very good. I’ve been through Igo Ueno, and I’m just trying to … I’m picturing a precession-

Fr. Roberto: Yes. In the city.

Fr. Joe: In the city.

Fr. Roberto: On the streets. Yes, and then we have other occasions, such as we want to renovate the parish, we want to make it bigger. Because of the new Catholics, it’s no longer capable to feed as many Catholics as we have, let’s say for Christmas, Easter, Ash Wednesday, and other big faiths. So we have begun an annual festival for the parish, where we have international food from Indonesia, Vietnam, Peru, Brazil, Japan, and others, and we have the parishioners providing dancing, and singing, and we have a Bazaar, which everything is donated to the parish so that we can sell it. We have a sandwich and coffee corner, we call it Kids Corner for them to play all day long. And so we’re making the festivities, and for them it’s home. I mean, it relates to what they have experienced in the past. The festivity, I mean. You know, the games and the dance.

Fr. Joe: Are your services multi-lingual? Well, so you have like Portuguese, Español, and Japanese.

Fr. Roberto: Okay, we call them international masses, the ones that you are naming. The routine within the parish of Vigo where not every month flows this way. Every Sunday I had regular Japanese mass for the Japanese community, more others who come, you know, but on Saturday, and we do this Saturday night at seven 30 because migrants work all day long, Monday to Saturday until six seven, eight P.M. So the 7:30 PM hour was put on Saturday for those who wanted to go to mass but couldn’t do it on Sunday because Japanese do work also on Sunday and like unlike other countries. And so the first Saturday we have liturgy in English. The second Saturday we do it in Portuguese. So I do it in English, Portuguese, that’s our Saturday.

We have our Japanese mass that is here for the children, which are mixed marriages. So the children’s are bilingual, let’s say English, Japanese, Spanish, Japanese. So for them, we had this mass that our Saturday month and the other Saturday we do it in Spanish, so we cover four Saturday, four weekends of the month on those diverse language. Plus. I have another priest friend of my friend, the Philippines who comes and do the Tagalog mass, the third, the fourth that Sunday or the month. So we have liturgy on those particular languages five on five occasions given a month. I do the Portuguese, the Spanish, the English, and the Japanese because I have another Portuguese mass that are Sunday at the math.

Fr. Joe: Now, how have the Japanese, either parishioners or not parishioners reacted to the influx of immigrants?

Fr. Roberto: Well, now we have a Pentecost church, if I can call it like that. We do and everybody now is okay, but it’s been thirty years that this process has been in place. It was begun by other missionaries. I just happened to come at this time. I’d been there three years now and it’s really a Pentecostal church. I don’t mean in the denomination of things, but that is mixed and he has come to be now, this is the way we are now. It has been a struggle.

I remember the meeting I attended with the council, the council has quite a large number of representative from the Japanese, the Peruvian and the Brazilian, all of them. And the big argument from a parishioner who was Japanese was that why were the Peruvians putting flowers in front of the statue of Mary and Joseph is not a big deal. I mean really for us who come from that sense of flower saying it. Yeah, all of that. But before the Japanese, this sense of aesthetics and beauty is the simple, the best. They’re most little the better. This silence instead of talk. Great. And so it was touching and up on this particular version. That doesn’t mean that everybody should. But she was a representative for the so called liturgy component of the parish and she was really saying “I don’t understand, one flower arrangement only she said in front of the Delta. That’s plenty.” But what the Peruvians bringing flowers to Mary is as the, as she is for the Japanese silence, you know, and no work. So that is where they saw that tension of these two communities. Both had good things; I mean both are valuable, wonderful liturgical sense of what is appropriate and good for the Japanese one flower arrangement is all you need, which is what you will find in every house of Japanese one flower Ikebana in the corner where people don’t go by because they say beauty is to be appreciated. So you have to look for it. Well for Peruvian, Mama Mary is a matter of God so we bring in flowers every day, you know, every weekend.

So that tension happened and it involved the whole community in the end we come to, it doesn’t really matter if we had three rather than one flower arrangement. But that’s the tension that, I mean that’s a small little thing, but that’s where you see the two cultures do clash. And like that I know we have argued about sitting places and best men, dressing, and all of that because it touches the heart of the individual. Both of them are correct. None. None is better than the other, but it’s a matter of give and take, give and take in coming together, coming together. I just think that by now we’d really had done a great job. Certainly, as I say, the Bishop has said so to my regional superior and he has communicated that to me that he’s very pleased with the way the church is run and is developing because he said that he’s a witness to Japan or to the area or the races or what he would like. [inaudible] which is good. That means that he’s all in favor.

Fr. Joe: And the bishop is Japanese?

Fr. Roberto: He’s Japanese, yeah. All bishops in Japan are Japanese. This one in particular that, well that’s very good. That means that he understands. He cares for the migrants. He had written about caring for the migrants in Japan.

Fr. Joe: What about the Japanese population in general is any backlash to all these foreigners?

Fr. Roberto: Just like in the parish, I read in the newspapers, I hear it in the news the same tension, but upgraded level, you know for some they had the sense that perhaps those who come from other countries are not as respectful of the cleanliness [inaudible] sense of honor or duty or commitment, which they hold very dear until they often you hear demeaning commentaries [inaudible] why are we open the borders to others so to speak. And you know, it’s not a blank resistance, but there is a sense of the country changing and they don’t like it. So that is there.

Fr. Joe: Universal?

Fr. Roberto: Yes, very much. I like that.

Megan: Japan hadn’t had immigration, right? Weren’t they? They like hadn’t had open immigration for a few years or something? I thought I had read or something.

Fr. Roberto: These reality of the new migrants permitted, those who come to work began at the end of the 1960s or the 70s.

Because Japan after the war, which was totally destroyed, except a few places like Kyoto grew, expandedly and became the second economy in the world, they were powerful economically. So in order to continue sustaining this level of economical development, they needed labor because Japan was, was beginning to decrease in population and they saw they need [inaudible] to have more people work. So they offer the initial opening to Brazilians and Peruvians and Bolivians before others because there, they were descendants of Japanese people who migrated to this country at the beginning of the 19th century because Japan at that time was lacking, was very poor.

And so, Brazil offered to those Japanese, I understand that 100,000 families from Japan left from Nagasaki, I think, to Brazil because they were offering land as long as they work the cane sugar. So that was the incentive, and likewise to Peru and Bolivia. So the migrants that I’m talking about are the third or fourth generation, they send an old Japanese who went to Brazil to Peru and Bolivia where we have colonies of Japanese. Okay. So now after they did that and it was successful because all of these companies were producing for the same, they needed more and so they diversify and so they opened it to the Filipinos, for example, in Muslim where women, they were brought into what is called the entertainment industry, meaning all of that that is involved there. And then eventually they began bringing people from other countries.

I think the reason is because that way is more diverse perhaps or especially agreements with these countries. So now we have people primarily from China, from Korea, and also the Philippines. I say Myanmar, Bangladesh, and Vietnam is the last one. They come under the the rubrics of working/training is the program they call it.

Fr. Joe: So they go back?

Fr. Roberto: They have to.

Fr. Joe: They have to go back?

Fr. Roberto: Okay, so we have two type of migrants in Japan right now, the first are enumerated because they are descendants of Japanese, three or four generations before. They can remain, they can remain. So they can work towards permanent residents or even citizenship. These ones that I brought in who are no longer descendants.

Fr. Joe: Not Japanese at all.

Fr. Roberto: At all. They just migrant workers, they come under what I just call training program and they are given a working visa. People said, I even agree with that, that they are brought in under this rubric [inaudible] because that way they don’t have to pay the full payment that the law required for that regular working because they are receiving training, they’re receiving. But really they just go to the factories and they work. But because they are trainees they are paid somewhat less in the same the benefits. So at the end of the five years, So last year a law was passed that they can now renew it for another five. So this workers basically come to Japan, let’s say from Vietnam, from Bangladesh, after 10 years.

Then they have to go back unless they get married to a Japanese woman or men. Then they can work what I stay in. But the majority have to go back because they are all single. They are all young people in their 20s.

Fr. Joe: I was going to ask if these migrants have children in Japan are the children considered Japanese?

Fr. Roberto: No they’re not.

Not at all unless I guess the mother is Japanese and then she will claim it. But just because they are born, unlike in the United States you do not receive any benefits to be a resident permanent, or a citizen and I just mentioned all of them are in their twenties late teens. So they are single like the Vietnamese that I’m receiving, I have now quite a lot and I’m thinking how can we provide for them at Vietnamese language service, you know, so I’ve been trying to pull up priest that I know here and there but they are also very committed to other works. So they are very, very young men and so they produce quite a lot. But again, they are at disadvantage that because there are no descendants of Japanese and they are being trained, they are, they are not paid the full amount that shouldn’t be the case in most cases, you know, maybe 10% less or whatever and the benefits also, but in comparison to where they come from, they are much better off in Japan and they saved money and they do send money home, you know? So that’s a blessing so to speak.

Megan: I want to go back to what you said about the procession and how..

Fr. Roberto: Oh those are wonderful.

Megan: Yeah, how you couldn’t see where was the city? You said you’ve been there and then you’re just trying to like envision..

Fr. Roberto: Ueno, it was in Ueno.

Megan: Is it just because like what Father Gerda said where it’s more quiet and still?

Fr. Roberto: The Japanese have festivals. They have festivals for harvest [inaudible] for many kinds of reasons. So there are not estranged to festivals. In fact, I think that they enjoy them more so than not. However, because this is religious per se, Christian Catholic, they mentioned that we do it on the streets is totally unusual for them to see.

Megan: But Japan is primarily Buddhist, right?

Fr. Roberto: Both, it’s Shintoism which is original traditional local developed sense of religion and Buddhism which, came into Japan in the sixth century. Through China, in Korea.

Fr. Joe: And I’m, I’m thinking while you were saying that, you know, in Williamsburg, our lady of Mount Carmel, every year near the feast of a leader in karma. It’s this huge tower, weighs tons I guess. And the men carry it through the streets and they do a dance and I’m Italian, I’ve never seen anything like that. And I’m like, Whoa, what does that have to do with anything, you know? So I can imagine what the Japanese think when they see this [inaudible] carry statutes. Describe what the precision looks like.

Fr. Roberto: Our lady of [inaudible] has a rather small image, which appear [inaudible] after the Portuguese came in and there was this fisherman who was fishing and instead of getting fish, he caught the image, they don’t know how he got there, but he got it and he was, this is the sign we’ve been waiting for, God is with us, this is the mother of God. So [inaudible] is the biggest religious festivity for Brazilian. So it’s very [inaudible] to remember that and to celebrate it every year. So what we do is we have, we be in there, there with prayers, singing, the Holy Rosary, and then before mass we process. So we have a special ketorolac..

Fr. Joe: Like a bier, B-I-E-R, a platform!

Fr. Roberto: A platform, and that women and children they fight to carry. They do. I mean it’s like, I mean, you know what I mean is they feel that it’s a blessing to receive. So we go along several blocks where the parish is located, aren’t and we’re singing, we are praying and you can see the devotion, we hold candles in our hands, flowers in our hands. And so we come into the church and the festivity just go on into the liturgy, which is quite elaborated. I mean it’s really not your regular Sunday mass, but we have incense and we have bells, and we have servers and we had this and that. So it’s a very festive day. And of course after that the party begins, which is everybody brings food, everybody brings home, you know, Brazilian food. And I had tasted foods that I never knew existed, you know, delicious.

Adam: So my, my response to when he was saying this was because I’m thinking of a omikoshi matsuri yes. And it’s in Japan that the different neighborhoods will, will take from their shrines, they’ll take the Kami and they’ll put them on these long posts and the entire neighborhood gathers around the Omi Koshi, which is a float and then exactly what he’s saying. It’s the same thing just changed. They changed the statue and they March it through, but then they, they parade it and it’s a huge party. But then the different, the different Cami or the, the, the omikoshi will face each other and they rock them back and forth. And it’s almost like a battle among the gods in the middle of the street. And it’s a huge, massive festival.

Fr. Roberto: The one in Kyoto are amazing, thousand people that come from all over.

Adam: And I think it’s fascinating because that’s what the Japanese must be thinking.

Fr. Roberto: That’s why I thought.

Adam: That’s what Omi Koshi does.

Fr. Roberto: That’s what I thought. If they had the San Francis savior continue his ministry or he had not gone to China because he was baptized in the first three months, he baptized close to 30,000 Japanese. Him and his companions, I mean, not just him. You know, Christianity was rising like a wave of the greatest caliber, from one day to the next, he said, no this has stopped because then we will be a colony of the King of Rome. So you know, Japan close his door to all foreign, the Dutch were [inaudible] back to Europe, same with the Portuguese.

Adam: And not the Orthodox up in Hokkaido.

Fr. Roberto: Correct. Correct. So that’s the appendix to their story. But everyone else left. So for 160 years, 203 years, there was no contact with the West whatsoever. It was totally close until it was reopened in the 18th century. If that did no happened, then Japan would be the most [inaudible] country in the world. Because when they take something in, they not only take it because they accept it, they see all these potential in qualities in good thing, but they make it a better, you know, so they would have been the most Catholics in the world, but they were prevented from doing so, you know, because like the Philippinos at Greek Catholic, the Italians at Greek Catholic, you know what I mean? But the Japanese would have taken it even more so, and then they would be very harsh and disciplined during the rosary, and doing this to it.

Fr. Joe: State’s exhibit number one. I look at Korean Catholic church. If you’re going to do it and do it fanatically.

Fr. Roberto: I am very, very sad when I reflect on that. But at the same time, God somehow let it happen. So God knows what is going on, yes.

Megan: Right. Great. So tell us about how you got to Japan and tell us a little bit about that journey.

Fr. Roberto: I began with Maryknoll when I was in my twenties I was a migrant from El Salvador who came to the United States in work in a foundry in Texas where he was a very hard labor work. However, after a year and a half there, I felt that I needed to do more to study English, for example, improve my sense or where I was going. So I moved to California. It was during the years of President Reagan and the situation for migrant west, no as bad as it is now, but it was quite bad and unemployment was very low. So with another friend, we travel from California all the way up to Washington state where we decided to go across to Canada because we had heard.

That kind of was welcoming refugee from Guatemala, El Salvador due to the civil wars in Central America, which is the reason I also migrated myself from this harbor to the U.S. And as I was traveling from the Los Angeles area to Canada to Washington state in Seattle, I went to a regular Sunday mass, the only Spanish mass at that time, this is 1983 the praise was a new missionary priest making a mission appeal. He had been working in Bolivia for quite some time and he described his missionary work with the tribal people along the river, the Benny river, close to the Amazon. And I was inspired by his talk, his work, his testimony.

I said, well, that’s what I wanted it to be.

Megan: So wait, so let’s take a step back. So you’re on your way to Canada. You stop in Seattle and when you’re at this random. Wow. So this completely unplanned church, completely unplanned service. You go in there and there’s a mirror, right?

Fr. Roberto: Correct. Previous to that only, I will just add that while I was in Texas, as I mentioned, and before working as in a foundry factory, I went to mass to their local church there and there I saw the Revis de Marino. So I pick it out once and I read about Brother Tony Lopez so that put Marino within my mind. Previous to that when I was a child, I want it to be a priest, but not necessarily a missionary priest. So when I’m in Seattle, I decided to be a priest, knowing Marino or Revis de Marino and now meeting this priest sort of like food, the whole thing together for me I said that’s what I wanted to do. But at that time, because I was not legally registered in the United States, after talking with him and some other people who helped us Salvadorians moved to Canada, I went to Canada because that was their recommendation. Go to Canada, get settled, get your legality in place and then give us a call.

So four years later when I’m in Canada, ready for four years, I called Maryknoll in Seattle and I told him I went to renew my contract with you and if possible, enter Marino. So they brought me to Seattle by the time I was already a permanent resident of Canada so I can travel. And so we had the vocational interview, they did all my life review, academic background, psychological testing, all of the things that we do for someone who comes into us. And then I was told that I, I could participate in a Hollywood retreat in Los Angeles in 1987, which I did. And they are, they told me that I had been accepted with Marino. So they, they find that Bob Lloyd, who was the vocational director, told me that although I spoke some English for academic work was very limited. So they asked me if I would go to the St. Joseph College seminar in San Francisco to study English for a year and I said yes. So I went there, I studied English as a second language for the first time, very formally. And I graduated from there. And came to Marino New York to do at that time what we would call the orientation year.

Then after that I moved to Chicago. I was the first man in order to go to Chicago and do my theology at Catholic theological union, and in between the four years of theological school, I was sent to the Philippines as a seminary, what I gave my overseas training program. Then in 1995 I was ordained here, in Marino New York, and sent back to the Philippines as a priest where I worked for two years and a half. Then after that I come back to the United States. Finally, Bob Carlton, who was the director of the department, said that I could work either in Chicago, Houston, or Los Angeles. So I chose Los Angeles because of the familiarity of the people from El Salvador, Central America, they’re more so than other places, and I went there and for almost 10 years I did mission promotion for Marino and vocational work.

And then soon after I finished that I was given a year to remain in the states and then sent to Japan. So since 2009 I had been in Japan.

Megan: Now did you choose the Philippines originally?

Fr. Roberto: Yes, yes. That was my young preference and so what happened is after I finish my missionary work, my promotion missionary work in the states, the Philippines was no longer a priority for us because their vocations are booming and so we were withdrawn for that country. So Japan was [inaudible] and I was happy to take it.

Fr. Joe: I think some people have a question saying the mission priest in one of the most technologically advanced and industrious countries in the world, why do they need mission priests there? We can understand 60 years ago or even pre-war Japan, maybe to some level, but could you answer that and talk about what are the needs for a Catholic mission? What does it, what are the needs of the Japanese people or the migrants fundamentally in Japan to have there be a reason for mission?

Fr. Roberto: I would say that’s perhaps one of the most interesting question when it comes to our presence in Japan, not only as missionaries but as the Catholic church; and I would like to quote here, Mother Teresa, who a long time ago said that Japan did as you say were potentially an extremely well to do country, technologically speaking as well as economically speaking, however they more than other people because of that influence of so many material things needed the spirit or dimension because they are by nature very sensitive to their spiritual dimension. That’s why the great respect for nature is based on that sense of respect for what surrenders. Buddhism calls for people to be mindful of the other, not to be resentful and all of the things. And Mother Teresa used to say that we needed to be more so than other countries because to feed the poor when we can do it, it is physically a moment of grace, of a friendship and love, but to feed the person who’s hungering for God or for the spiritual is much more difficult.

It’s much more demanding and I think that’s the the challenge that we face in Japan is really how do we present the message of love or forgiveness or reconsideration in kindness from Jesus Christ to the Japanese people. And I think that they need it more so. Their influence of their money is so much that people are giving to a lot of unhealthy behaviors such as champagne or gambling or drugs or because we do have all of those problems in Japan despite all their wealth, because they cannot afford it. And also, as we have mentioned in different moment, Japan is an extreme, rigid, very disciplined, demanding culture all ways of life, everything in life. And so a lot of times I find that many Japanese are really, they strive with that sense of duty, hard work, determination, but many are very gentle and soft and kind and very in cannot handle all of that.

And so they go in, they withdrew within, and then I see in them loneliness, sadness, I see them depression and many other manifestation of even schizophrenia. If your world, you know in the trains where you see the, you see them extremely tired from working 14/16 hours a day, not resting enough, right? And so we said that in the past, if I do have any, has a break or five minutes, he or she will stand in his sleep so that she can recuperate somewhere. And so I think that that country or don’t has all this money and technology is much more needed or a lot of presence of you know, that we belong to God, that we are of God.

That there is another way to be perhaps a human person if you will, and in the light of Jesus Christ who is gentle and is soft and is kind and is merciful and good.