by Adam Mitchell | Sep 20, 2019 | Podcast

We’re here today with Karen Bortvedt, who is the Recruitment and Relationship Manager for the Maryknoll Lay Missioners.

Karen coordinated various immersion trips while in college – including one to Nicaragua. She served with the Border Servant Corps for one year and has since worked with various non-profit organizations.

She worked at the Deaf Development Program as the Communication Coordinator. On any given day, she was found developing the communications strategy; documenting DDP’s many activities through photos and videos; visiting the provinces to document the field work of DDP; ‘playing Facebook’ as they say in Cambodia to share DDP’s work; writing blogs; creating mini-videos about the Deaf community; welcoming visitors; or coordinating volunteers.

You can check out more of Karen’s work by liking the DDP Facebook page, following them on Twitter, or reading the weekly blog updates.

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

Megan Fleming: So we’re here today with Karen [Bortvedt] who is the recruitment and relationship manager of the Maryknoll Lay Missioners here at Maryknoll and Karen was a Maryknoll Lay missioner in Cambodia and we were just talking about some of her experiences as well as Father Joe’s experiences at a 50 cent beer place.

Fr. Veneroso: Oh, definitely. This is in the village of Siem Reap.

Megan Fleming: Yep, Siem Reap.

Fr. Veneroso: If I’m pronouncing it … You fly into there if you want to go to the Angkor Wat, which is one of the wonders of the modern world, believe it or not. Not the ancient world. The modern world, the old old ruins of a once great temple that was part of a great empire. But tell us about your time in Cambodia before we get into your stuff you’re doing now.

Karen Bortvedt: So I went to Cambodia in 2014. When I was accepted to Maryknoll Lay Missioners, didn’t know where Cambodia was. I had looked at the different regions and was drawn to Cambodia because I wanted something that would stretch me. So I had studied Spanish, I lived on the U.S, Mexico border. So in my head I said, “I don’t want to go to Spanish speaking country. I want something that’s going to be a challenge.” The Cambodian language, Khmer, is not a Roman based language. So I ended up going with Cambodia and flew on a plane there having never been to Southeast Asia before and was in for all sorts of adventures.

Fr. Veneroso: What stretched you in particular?

Karen Bortvedt: I think the language was definitely sort of the mental stretch I was looking for. I think Cambodia is … It’s a primarily Buddhist country and so being in a primarily Buddhist country, some of the sort of cultural norms and cues that exists coming from a country that’s predominantly Christian were different. So getting to learn about that aspect and those perspectives from those I worked with. Then I actually ended up working with the Cambodian deaf population. So then I learned Cambodian sign language as well when I was there, which for me, I love languages and so it was sort of like mental acrobatics when whoever came up to my desk, I could be speaking in English, it could be Khmer, it could be Cambodian sign language. There could be two people who didn’t both understand the same language, so I’d be interpreting while being a part of the conversation and it was challenging and fun and I miss it a whole lot.

Fr. Veneroso: What impressed you about the Cambodian people?

Karen Bortvedt: Oh gosh. Cambodians that I encountered were very welcoming, especially the Cambodian deaf community, which is where I spent a lot of my time. A lot of the folks that I worked with hadn’t had formal education until they were in their teens, so they didn’t really have a shared language with a lot of other people until that point. But when I came in somebody from a different culture, from a different background, someone who was hearing, it was just assumed I was going to be one of their friends. So they worked really hard to explain their language to me and to put up with my terrible charades before I knew the formal language so that we could communicate. Anytime there was a holiday or we had time off work, they would invite me along and include me in things, especially the holidays when you were supposed to go and spend time with your family or go back to your homeland, I would always have this list of offers from people because they knew that I couldn’t go home to my homeland and so they wanted me to be included in their holidays.

Fr. Veneroso: That’s great. Yeah, I dealt with Buddhist culture in Korea and in Thailand. I’m presuming, but we will clear this up if it’s the same, where being born with a handicap is some … It’s kind of fatalistic, it’s karma and there’s almost a resistance to helping them. Did you find that?

Karen Bortvedt: That’s something that I had heard that existed that people would believe that their child was paying for something they had done in a past life and that’s why they were born deaf and there just wasn’t a lot of understanding around deafness. Even a lot of the families, they didn’t learn sign language even when their loved one learned sign language because they didn’t have an understanding of what deafness meant. So yeah, it was an interesting dynamic. It’s interesting though because even within the U.S there’s a lot of times where people don’t make the effort to learn sign language when they have a deaf family member. So it was hard for me to separate how much of that was related to their Buddhist background as opposed to how much of it is just a lack of understanding in general about deafness.

Fr. Veneroso: Here’s a question. Does the signing in Khmer translate to signing into English or does a whole different-

Karen Bortvedt: They are different languages.

Fr. Veneroso: Different word order or a sign order, I should say?

Karen Bortvedt: Yeah. I’m not fluent in American sign language, which is what we use here in the United States and so I can’t really do justice in terms of the comparison between the two. But each country typically has their own sign language and some countries have multiple sign languages, just like some countries have multiple spoken languages. The idea being that a sign language evolves from the culture in which it exists. So for example, the sign for girl in American sign language is if you stick up your thumb and sort of run it down your cheek like a bonnet string, because women in the U.S used to wear bonnets is my understanding where that comes from. Whereas in Cambodia, there would be no cultural reference for that. Women didn’t wear bonnets in Cambodia, so they sort of place their hand on the top of their head and bring it down to their shoulder indicating long hair.

Fr. Veneroso: It’s the hair? The long hair. I’ll try one. I’m placing my finger to the palms of each hand. Does that mean anything?

Karen Bortvedt: That means Jesus in American sign.

Fr. Veneroso: You got it.

Megan Fleming: There you go.

Fr. Veneroso: Now that’s the American sign language. Jesus in Korean sign language is pounding your fist through your palm, which is pounding the nail. But we did have a man working with sign language and within I would say an hour he was able to make the translation so it was much easier to go from sign to sign than from English to Khmer.

Karen Bortvedt: Yeah. That’s one of the things that I was astounded by with my deaf colleagues, is you could put them in a room with people who were all using a different sign language and they would figure out how to communicate. Whereas if you put a bunch of us hearing people in the same room, we go to our separate corners and pretend we don’t see the other people who speak a different language. The ability to connect with others just really blew me away and was very sort of inspirational, especially as I was struggling to learn the spoken language and the sign language. I was like, “Okay, I’m following their example, and just trying and you figure it out.

Fr. Veneroso: What would the deaf people do with their lives?

Karen Bortvedt: It’s evolved. So when the project was first started by Father Charlie Dittmeier who was serving as Maryknoll Lay Missioner at the time, but as a priest out of Kentucky about 20 years ago, there weren’t a lot of opportunities for jobs, for income, for those sorts of things. So many of the deaf folks that I met would have just stayed with their family if they were lucky, maybe helped with a family business, helped growing rice or whatever crops the family had, helped sending the animals. As more and more folks are getting education, there have been a lot of job opportunities in cafes. There’s a law in Cambodia that requires a certain percentage of your labor force be people with disabilities.

Fr. Veneroso: Oh, good.

Karen Bortvedt: It’s enforced to varying degrees, but from what I’ve heard from my colleagues that are still working there, those companies have realized that hiring deaf people works well for them because most of the folks they’ve hired are good workers and they have a desire to work and they have a desire to have an income and they’re dedicated to their work. So their only disadvantage is that they can’t hear and they communicate in a different way, but if they teach their hearing staff sign language, then they can be very successful in those jobs. So that has helped to increase the opportunities for deaf Cambodians. Some worked in factories, some learn different skills. There’s a barber training school at the deaf development program. Some do make up because for every wedding, if you are a woman, you have to have an extensive amount of makeup applied to your face. So weddings, funerals, hundred day ceremonies after someone dies, all sorts of things. So there’s a constant demand for cosmetology.

Megan Fleming: I think the project that he started, correct me if I’m wrong, has been pretty successful in Cambodia.

Karen Bortvedt: Yeah, we’ve had … I don’t know the numbers off the top of my head anymore, but each year they have the basic education classes that come through. Folks get two years of basic education, they do job training, they have interpreters. The problem that they’re facing now, which is sort of a good problem in the long run, is that a lot of our staff are getting hired on by other organizations. So our interpreters are getting picked up by other places that want someone with an understanding of Cambodian sign language. So they take all of our employees away and then we have to train more. So it’s bad for our organization but great for the Cambodian deaf community because it means more organizations and groups are getting engaged with that population.

Megan Fleming: So from a Maryknoll Lay Missioner perspective, is that sort of the main area where you guys will first send Lay Missioners? Is Cambodia one of the higher options or places of need if you will?For new Lay Missioners?

Karen Bortvedt: We definitely always need folks who are willing to go to Cambodia. At least when I came in, if you requested or had an interest in Cambodia, that’s where they would send you. Because as we were talking about a little bit beforehand, Cambodia is very warm. It’s over 90 degrees most of the year, 70 to a hundred trillion percent humidity. It is hot. So it takes a special person who can put up with that heat, and a lot of people are intimidated by the language and will tend to be drawn towards a Spanish speaking country or even one of our countries where they speak Swahili because they feel that’s more accessible.

Megan Fleming: Right.

Karen Bortvedt: So if someone is enthusiastic about Cambodia, we are enthusiastic to send them there.

Fr. Veneroso: Over the decades, Maryknoll Magazine has run various stories about Cambodia and one of the problems, I’m not sure it’s ever been resolved, is that of land mines. Is that still an issue?

Karen Bortvedt: As far as I understand, having not worked directly with landmines, the number of landmines are decreasing and they are clearing them out. One of the challenges is Cambodia floods every time the rainy season comes. So farmers will think their field has been cleared of land mines and then the water comes in, it moves things around, it moves new things into their fields. From what I’ve seen on maps, it’s sort of being reduced to smaller and smaller areas because there are NGOs that are working in collaboration-

Fr. Veneroso: And unfortunately they’re decreasing because a lot of them are exploding.

Karen Bortvedt: Yeah.

Fr. Veneroso: That’s the other thing. This came under the topic of the war doesn’t end just because the war ends. The casualties to the work can continue tens of years later, if they survived the explosion, the amputees and whatnot.

Karen Bortvedt: Yeah, I think the numbers are decreasing. There’s a Jesuit project that works there specifically with people with disabilities and historically they worked with amputees or folks who had suffered from polio, things like that, had different physical limitations. They’ve had to sort of shift their focus because there just aren’t as many of those people so they don’t have a full class, shall we say, of people coming in, which is great. It means polio is decreasing. It means there’s fewer landmine.

Fr. Veneroso: How long were you there?

Karen Bortvedt: I was there three and a half years.

Fr. Veneroso: So since I was there like three days, you can give me an insight. The thing that did not compute in my mind, I’ve visited a couple of the killing fields and you meet the people and they’re so gentle and so happy. It’s like how did that evil come out of these people? Do you have any insights into that?

Karen Bortvedt: I don’t. I mean, it’s one of the countries, from my understanding, that is showing signs of third-generation PTSD so there’s sort of been the suppressing of that experience. Father Kevin, one of our Maryknoll priests, works with mental health and there’s a lot of issues that sort of come up because that hasn’t been processed. I mean, I don’t know if it was desperation. What can lead to that? I think around the world where you see situations of genocide, what leads a group of people to that?

Fr. Veneroso: Exactly.

Karen Bortvedt: Some of it could be fear, some of it could be different things. Following the wrong person at the wrong. I’ve heard lots of theories, but many Cambodians don’t want to speak about that time. It’s not something … It’s too raw.

Fr. Veneroso: It’s too raw, exactly. Yeah.

Karen Bortvedt: Especially in the U.S, that’s something I’ve found time and time again. I’ve always very enthusiastic when I meet someone who’s Khmer or someone who’s from Cambodia. But I have to be very careful whether or not I bring it up because for many of the people, especially couple of decades older than I am, they came out of Cambodia during the time of the genocide. They were in the refugee camps. Whereas Cambodia for me is a place I love, for them it’s a place that they fear and that they ran from.

So it’s an interesting balance even figuring out how to continue to be connected with the Cambodian community here in the United States.

Megan Fleming: Walk us through how you first heard about Maryknoll and I’d love to know, you’re headed to Cambodia and let’s say you google it and you see the weather temperature is like Father Joe talked about. What were the feelings going through your mind when you first found out you were going to Cambodia?

Karen Bortvedt: So I first actually found out about Maryknoll Lay Missioners back when I was 18. I had done a short term mission experience and I told my youth minister I was just going to lose my passport so that she had to leave me in Mexico because I had so much fun just talking to people and hearing people’s stories. Lucky for her, I didn’t actually abandon my passport. She got me back to the U.S and said, “Hey, this group called Maryknoll” I think it was the affiliates, “We’re going to be speaking at the church.” She said, “You should go check them out. You might be interested.” So I went and at the time I said, “Three and a half years? There’s no way I could be away that long.” Then those seeds sort of get planted and keep coming up. So when I ended up applying to Maryknoll Lay Missioners, I think my family was very uncertain about that life decision. Most of my friends thought it made perfect sense and they were like, “Oh, of course you’d do something like that.” Then when I found out that I was going to Cambodia, I remember I was sitting in my little cubicle, I was just temping at the time and my coworkers knew that the call was going to be coming. So as soon as I got the call I went running through the office and I was like, “I’m going to Cambodia!” and then had to explain to most people where Cambodia was. But it’s one of those things, it’s hard to process exactly what you’re getting into. What does constantly being in 90 plus degree weather with 90% humidity actually feel like? I feel like until you’ve lived through that, it’s hard to understand the extreme heat that is there. But I think initially I was really excited and there were definitely ups and downs throughout the mission time. But I think life sort of has those ups and downs. It was just in a different context and I was very lucky to have the Cambodia deaf community and have other Cambodians that were a part of my support system and my community. So that when I did hit those down slumps, like finding out my head was infested with lice, there were people to pick the nits out for me, shall we say.

Megan Fleming: I guess before that, did you always have an interest in volunteering and sounds like you did that short term mission trip. Did you do anything when you were younger? Were you always helping people? Did you always have a knack for different languages? What sort of brought Karen to be Karen?

Karen Bortvedt: To Maryknoll Lay Missioners?

Megan Fleming: To Maryknoll, yeah.

Karen Bortvedt: I was definitely always a volunteer kid. I was homeschooled, which was nice in the sense that I had all this free time and I chose to spend it at the elementary school after I was in middle school. So I volunteered at the elementary school starting in sixth grade, all the way up through high school. In high school I was a weird volunteer kid. Everyone else was at the football game on Friday night and I was over at the elementary school volunteering or at the retirement home or running can drives. I was a part of key club, which is connected with the Kowanas. So service was always my thing. Especially when I started in college, I started to really see how service could connect with a deeper encounter and build on that. I studied political science and Spanish in college because I was interested in migration and where I grew up, migration looked like farm workers who were from Spanish speaking countries. So that sort of led my major, and then throughout college I did different service learning trips. I worked at the service center. I pretty much went in my freshman year and said, “I want to work here”, and they said, “Well, we don’t have any jobs”, and I said, “Here’s my information. I want to work here.” So second semester freshman year, somebody had resigned and so they called me up and said, “Do you still want to work here?” So that was sort of how my path had evolved. I did a year of post grad service with a Lutheran organization called [Borgia] Servant Corps in El Paso, Texas, and then went on, as I tell people, I tried to join the real world for three years, but still working with nonprofits or universities the entire time. Then was really looking for something that would get me back in a place where I didn’t have to keep faith and service and daily life separate. Because I feel within our culture we’re taught to compartmentalize everything, and that’s just not who I am. I like everything to be interconnected. So coming back to Maryknoll Lay Missioners gave me that opportunity for everything to be unified again and my faith could be shown in my actions in my daily life and I didn’t have to separate them out.

Megan Fleming: I was going to say, where did you grow up? So our listeners know.

Karen Bortvedt: I grew up in Hillsborough, Oregon, which is a suburb of Portland, Oregon.

Megan Fleming: When were you the … Now I’m trying to remember from NCYC when you were the biker, you were delivering messages.

Karen Bortvedt: I was delivering messages?

Megan Fleming: Weren’t you delivering packages on a bike in New York City or DC or something?

Karen Bortvedt: I did use to commute on a bike.

Megan Fleming: Maybe that’s what it was.

Karen Bortvedt: I’d just bought my first car 24 days ago.

Megan Fleming: You guys can’t see Karen, but Karen is this petite, shorter side, powerful young woman and I just am picturing her commuting in busy city streets and just rocking it.

Karen Bortvedt: I protested when I had to finally buy a car.

Fr. Veneroso: Your experience and certainly your positive attitude now makes you the ideal person to fulfill the job you are now in, whose title intrigues me. Say your title again.

Karen Bortvedt: My title is recruitment and relationship manager.

Fr. Veneroso: Recruitment and relationship manager. What does that mean in English?

Karen Bortvedt: I tell people it means that I get to travel around and make friends.

Fr. Veneroso: Isn’t that great? What a great job that is.

Karen Bortvedt: It is.

Fr. Veneroso: Now you’re recruiting obviously for the Maryknoll Lay Missioners.

Karen Bortvedt: Correct.

Fr. Veneroso: So for the sake of our listeners and those who may be interested, this is your time to give a call out to what people should do if they’re interested.

Karen Bortvedt: So our Lay missioners are folks from all walks of life. Our youngest missioner right now I think is 22 or 23. We take folks as youngest 21. Our oldest missionary is 78. So people from different age demographics, married folks, people with families. If folks are interested, you can find us at mklm.org. You can probably find my information through our website and we have all sorts of resources for discernment, discernment retreats. My phone number is up there. It’s a cell phone. So I always tell people, send me text messages. I’ve had an hour and a half conversation with someone once doing discernment questions via text.

Fr. Veneroso: That’s great.

Karen Bortvedt: We try to reach out to people and just help them as they’re trying to consider what comes next, and when they’re in that space thinking, “Maybe I want to do this, this is what’s holding me back”, and help them to really break that open because the more that someone has thought about that before their boots are on the ground in another country, the easier that transition will be. It’s still going to be challenging wherever you go, but if you’ve thought about it, it makes it easier.

Fr. Veneroso: How long have you been in this job?

Karen Bortvedt: A year and a half.

Fr. Veneroso: Have you found any differences in, say, region or age as to interest?

Karen Bortvedt: In terms of region within the U.S?

Fr. Veneroso: The U.S, yeah.

Karen Bortvedt: It’s fascinating. So this year I’ve been on both coasts. I was just in Alaska. I was in Oklahoma, which was a new place for me. It’s just interesting to see because everybody’s definition of mission is a little different depending on where you go. But a lot of times if we can introduce the idea of how Maryknoll’s mission, people get excited about that. They just didn’t know before we came there and that’s one of the reasons why I get really excited. When I got the invitation to go to Oklahoma, I was like, “Yes, this is awesome.” The person was like, “You realize you’re coming to Oklahoma, right?” I was like, “I’ve never been to Oklahoma. This is going to be great.” It was three days of multiple retreats and speaking at masses and just interacting with people and it was amazing because it was a lot of people who hadn’t heard of Maryknoll before, but we’re really excited about what it is we do. So those are my favorite parts of the job. There’s some places where Maryknoll’s more well known and those are easier places to go in a sense. But maybe it’s the missioner in me. Those are the places I want to go.

Fr. Veneroso: That’s it. We go where we’re not know.

Megan Fleming: Now do you have to be Catholic in order to join?

Karen Bortvedt: You do have to be Catholic in order to be Maryknoll Lay missioner. We have shorter term immersion trips that you can be of any religious belief, but for the longer term contract-

Fr. Veneroso: What would those entail, the shorter term mission?

Karen Bortvedt: The shorter term, their mission are immersion trips and so there are 10 days to two weeks and you go, you meet the missioners, you see the work, you go to places like Angor Wat and see them if you go to Cambodia, and so you get to learn about the countries where we serve, encounter the people we serve alongside and come back and hopefully help to build bridges between what you’ve seen and where you’re from, connecting places like Cambodia and Oklahoma.

Megan Fleming: Karen, did you have any kind of transformational experience in Cambodia that really was just a change in your life where you remember before that event happened and then your life after that event happened?

Karen Bortvedt: That’s a great question. I think one of the stories that I often tell was working with my colleague, [Leeka 00:21:41], who was one of our hearings staff members and she had been on staff for probably, I don’t even know, 10 years before I got there. And had this deep passion for working within the deaf community, but especially for helping to clear space so that the deaf voices could be heard. Because a lot of times they weren’t offered a seat at the table, but Leeka would stand up in meetings and just rail about sort of autism and hearing supremacy and things like that in ways that were not culturally normal within Cambodia or for a woman within Cambodia. So she’s just this fiery personality. She got promoted to a director role right around the time I was going to be leaving, probably six months, nine months beforehand, and she came to me one day and was really upset because of something that had happened and she felt like she needed to take it to the bosses. But within Cambodia there’s very much a hierarchy. You go to your boss, they go to their boss, they go to their boss. You would never just go straight to the top, which was something I had to learn because that’s not how I operate. But she was really upset about this and she was crying, and then she was laughing and then she was crying and I was like, “Okay, well what do you think you need to do?” She walked through it and I did what I did most of the time I was there, which was just kind of be a cheerleader and be like, “Yeah, that’s great, you should do that.” She was like, “I just don’t know”, and I said, “Well, do you want me to go and talk to the boss?” Because again, I’m an overly empowered woman from the United States who’s like, “I’ll talk to anybody and tell them anything that needs to be said.” But she looked at me and she said, “No, I need to be brave now because you won’t always be here, and so I need to learn to be brave now.” It still chokes me up every time I tell that story because that for me was what mission was all about. It’s about showing up and being a cheerleader and sort of being that support for somebody so that they feel empowered to use their own voice. So that would probably be one of the times that, as you can tell, still hits me in the chest every time I think about it and that she’s gone on. She still works there and is doing phenomenal work and oversees the child protection policy group and the deaf leadership group and all kinds of different things.

Fr. Veneroso: Now when you came back, usually when the missioner returns to the States, there’s a grinding of gears. There’s a reverse culture shock as we call it. Did you have that experience?

Karen Bortvedt: Yes. So I am not someone who’s good at slowing down. Also, probably a common trait among missioners I’ve met, but I was very intentional when I came back and had planned four months to give myself space. So I had lined up family members and friends couches for that time to create space to process. But one of the things … I mean the language was one thing that I found very overwhelming because I’d been used to working in a trilingual environment where it’s very easy to tune things out if you want to. Well, I came back to the U.S and so being in crowds where I could understand every conversation that was going on around me, it was overwhelming and I’m an extroverted person but I couldn’t handle it. One of the other things was very hard for me was being in spaces where everybody else in the room was Anglo because I had spent three and a half years oftentimes being the only Anglo in that group and so when I was in that space I was very uncomfortable and it was interesting to have conversations with friends of mine who don’t identify as Anglo because they wouldn’t even notice and I could tell you exactly how many non white people were in that room. I would walk in and could just … There’s two. There’s only one person and that’s what I’d usually say. There’s only one other non white person here and they’d be like, “You are white.” For listeners, I am white. I am very Anglo, but in my head I’d gotten so used to just being around all my Cambodians except when I was in Maryknoll gatherings, that it was a hard transition and there’s still some times where it makes me uncomfortable.

Fr. Veneroso: I remember coming back from Korea after … I think the longest was like four years when I was away, and going into my house and turning on the hot and cold running water and going, “Wow, hot water comes right out of the tap”, because it wasn’t that common then. Now of course Korea has a lot, but I’m sure in Cambodia too. You learn not to take those things for granted.

Karen Bortvedt: Yeah. A lot of our water was hot though because the water is stored on the roof.

Fr. Veneroso: It’s always hot.

Megan Fleming: I mean, even from the weeks, the month I should say, that I spent in Tanzania, I remember when I came back and that was for a much shorter amount of time compared to both of you. But I felt so selfish sort of. I had a lot of guilt where I came back to the States and I came back to obviously all of the first world things that we have access to and I remember going out with friends and they were just complaining about different things. I just remember sitting there quiet and I’m just like, “I can’t believe this is the conversation we’re having where people are complaining about first world problems.” It was a very hard transition for me when I first came back because I did, I felt a lot of guilt about it and I didn’t really know how to process this because I wanted to really … I don’t want to say smack someone, but I wanted to kind of shake them a little bit and say, “This is not the end of the world what you’re complaining about.” I don’t know if you guys had similar experiences.

Fr. Veneroso: Well, I remember coming back … Well first I was in the Peace Corps before I joined Maryknoll and it was in Korea. It’s such a life altering experience, and of course the people you go through this with, you’re a special bond there. So I come back and I got all this enthusiasm about sharing what I experienced and they’ll say, “How was it?”, and they realize that’s a rhetorical question.

Karen Bortvedt: Yes.

Fr. Veneroso: They really didn’t want to hear the details at that point. So you start by telling the story and you realize you’re losing them. You say, “It was fine”, but eventually, eventually that settles down and then they start to ask on at their speed, “What was it like?”, and then you get to share your story.

Karen Bortvedt: That’s the joy of working for Maryknoll, is I get paid to tell the stories people want to hear.

Fr. Veneroso: Isn’t that amazing?

Karen Bortvedt: That’s what I always tell people. I go to a church and they actually want the full answer, not just, “It was fine.” So it’s a good a way to transition out and hold those stories and continue to do that bridging.

Fr. Veneroso: The Holy father, Pope Francis, has called for a extraordinary month of mission. Is that what the title is, in October? What would you say to your average baptized Catholic about the duty to be a missioner, no matter where they are and no matter who they’re talking to?

Karen Bortvedt: I would say that it’s about encounter and deep listening. So it doesn’t have to be a world away. It can be the person you see walking down the street that you say, “Something about that strikes me as odd” or you might say, “Oh, that person seems a little weird.” I feel like is what we say a lot here. Instead of just having that thought, engaging and trying to learn.

Fr. Veneroso: Exactly. I know a lot of people think when they hear mission, you’ve got to cross the geographical border, but there’s a lot more borders out there that divide us. Racial, ethnic. Get out of your comfort zone. That’s the thing about being a missioner. You’ve got to leave your comfort zone and talk to the person or engage the person or listen to who’s different than you are.

Karen Bortvedt: Yeah, and be okay with disagreeing because you’re not always going to agree and you’re not always going to understand.

Fr. Veneroso: And they’re not necessarily going to be grateful for your coming over.

Megan Fleming: Anything else? Anything? All right. Thank you, Karen, for being with us..

Fr. Veneroso: This was fun.

Karen Bortvedt: Thanks so much.

by Adam Mitchell | Aug 30, 2019 | Podcast

Megan Fleming: Father Smith, why don’t you tell us about where you grew up and how you first learned about Maryknoll?

Father Smith: I grew up in Northwest Indiana, very close to Chicago in a town called Highland. It’s the same town where my father grew up. It’s actually the largest town in Indiana. I was there in the mid ’50s through the ’60s. That was for high school. Then went to Purdue University, also in Indiana, for my undergraduate work.

Megan Fleming: Growing up, did you live on a farm or anything like that, or was it more like just a city? It sounds like it might have been more towards a city kind of life.

Father Smith: Well, it’s a town, more of a suburb type because most of the people working in that area would be employed by the steel mills and the oil refineries. In fact, that’s how my father ended up there. His father was originally a miner and came from England, went to the iron mines in Northern Minnesota. He was involved in trying to form the first unions.

Megan Fleming: Wow.

Father Smith: God blackballed, so he couldn’t get a job. He then heard about this crazy guy who was paying exorbitant salaries over in Detroit named Henry Ford. He went over to Detroit to try out that employment for a while. The story in the family is, I don’t know how true this is, but they say he worked for one day. He didn’t like the guy standing over him with a stopwatch, so he said, “Nuts to this,” and he moved to Indiana, which is there the iron ore from Minnesota was shipped. My grandfather and four of his sons all worked in the steel mills. My father was the youngest of the sons. He also had a sister, one sibling younger than him. When my father was young enough that he was able to go to World War II, but at the middle of World War II, it was when he became 18 and he could join the army. That enabled him after the war to use the GI Bill. He was the first one in our family to get a college education, and he became a lawyer. Then he and his classmate from Notre Dame became the first two lawyers in our town.

When he retired some 35 years later, there were 50 lawyers in the same town.

Megan Fleming: It sounds like you could’ve gone a few different paths, right? You could’ve followed your father’s path of law, or maybe with oil, or the Army. Did you feel like you were being called to God, because I know you also have the business background as well in computer science. Walk us through your journey.

Father Smith: Okay. My mother was a scientist as well. She wanted to be a doctor, a medical doctor, but back then in the late ’40s, early ’50s, women were not being allowed into medical school. She even had the US senator for Illinois write a letter on her behalf to try to get into the state medical school in Illinois, and she was still refused. She went on to become a research biologist. Later on after getting married and having children, she stayed home to take care of the kids, as was the common practice in those days. When we were old enough, she went back to become a school teacher. She taught biology in the Catholic high school near our town. She had a big influence on my interests.

I grew up especially in school, high schools, enjoying things like mathematics, chemistry, physics. I started at Purdue as a physics major. After a while I switched my major to computer science. Later on I went to grad school at MIT in Cambridge, Mass and studied artificial intelligence. It was very unusual that Maryknoll was never allowed into our home Diocese of Gary. My understanding is the bishop was always afraid that Maryknoll would steal his vocations. So, I was never introduced to Maryknoll during my growing up, but as fortune would have it or fate would have it, the only Maryknoller engaged in campus ministry was at Purdue in the whole country, Father Phil Bowers. He was very active, very dynamic guy. I remember one weekend he brought in a team of Maryknollers, probably priests, brothers, sisters, lay missioners, to give a presentation at every mass. I thought, “Oh, these guys are doing good work,” so I signed up to receive the magazine and become a sponsor for $1 a month.

Through my college years, I would receive the magazine. I’d flip through it, look at the pictures and think, “Oh, yeah, they’re doing good work,” and send in my dollar, but I didn’t give it much thought till my senior year of college. I started thinking, “Well, now, what to do I really want to do with my life?” I guess having looked at the magazine enough, it made an impression that I did clip out a coupon in the magazine and send it in saying, “Yeah, I’m interested in some more information about a vocation to Maryknoll.” Before I got an answer, I had graduated. Then I moved to Boston, and there happened to be a Maryknoll house in a suburb of Boston.

I contacted Maryknoll again, and they invited me over. I started going over every month for a dinner usually at the Maryknoll house, talking to the missioners who were there, hearing their stories. After a couple years, I decided, “Yeah, I think I want to give this a try.” It was rather shocking news to all my professors at MIT.

Megan Fleming: I’m sure.

Father Smith: But they all assured me that I could come back if it didn’t work out with Maryknoll. I did go on a mission exposure trip with Maryknoll to have a better understanding of what I would be getting involved with. I spent three weeks in Guatemala, and it was a great experience. It was really helpful to have that experience before going to the seminary because it always gave me an understanding of what I was working towards.

Father Veneroso: What years were these, in the ’70s?

Father Smith: This would’ve been the summer of ’79 when I went to Guatemala. I wasn’t too aware of the political situation, but I do remember the drive from the airport to the Maryknoll house in Guatemala City and then later walking around the city a bit. I was rather struck by the number of military men walking around the streets with machine guns, something I’d never seen before in my life in America.

Megan Fleming: Right.

Father Smith: Most of the three weeks was spent in the mountains in very rural areas. In fact, one of the highlights of that three weeks was when I was paired with another young vocation prospect, and we were sent to a parish. Father Bob Crohan was the pastor there. He had planned for us to go off to some remote villages on horseback. That’s the only way you could get there.

The other young man got sick, so Father Bob had to stay with him in the parish. He sent me off with the Spanish speaking catechist with me not being able to speak Spanish on our horse journey overnight to another village.

Megan Fleming: Had you ever ridden a horse before?

Father Smith: Yes, I had.

Megan Fleming: Oh, okay.

Father Smith: That was fine. But just being among the people, and I couldn’t speak a word, it was a tremendous experience because I had to communicate in other ways. I learned a few words here and there. It was such a positive experience.

Megan Fleming: It a positive experience, but at the time were you scared? Were you nervous, because here you are going on horseback with someone you really don’t know that well, you don’t know the language, and you’re going up to the mountains of Guatemala.

Father Smith: I don’t recall being nervous at all. I was more excited.

Megan Fleming: Good.

Father Smith: I was really enjoying it. I was very happy to be there. I was enthralled with the faith community that I encountered, how they were celebrating, how they were welcoming me. We went off and had services, services without a priest of course, but prayer services. They always invited me to say a few words. I don’t know how much they understood, but they always were happy that I was there visiting their homes, sharing food with them.

Adam: You went from an institutional educational environment in technology to the remote part of the world where you didn’t know anything, anyone, literally from opposite ends of the spectrum.

Father Smith: That’s right. I really was enthralled with it, like I said. Later on when I was asked where I wanted to go for our overseas training period, I knew I wanted to go to a rural area. As I mentioned earlier, my mother being a biologist, I’d grown up experiencing nature. We would always go on vacations to natural wilderness settings. I most profoundly experienced God in wilderness areas, when I’m close to nature.

That’s why I really wanted to do mission in rural areas, again, being close to the land, being close to the trees, water, and being with people who live their lives like that, who have to farm, take care of the animals, things like that. When I went off to Africa, that was certainly the case.

I spent most of my years in very rural villages where I covered 2,000 square miles by motorcycle, 30 different villages, going out one village a day and then spending the day there after the mass visiting people’s homes, sharing meals with them, maybe blessing graves if someone had died since my last visit, celebrating baptisms, marriages.

Then blessing fields, blessing harvest, and seeing that despite how poor they were, their faith was incredible.

Megan Fleming: Father Smith, did you feel as if you had some type of transformation, because I’m picturing this young guy in college in graduate school at MIT, like Adam said, doing very strict academics and things like that, to total change where you’re in rural Tanzania or Mwanza, riding a motorcycle with no road signs. I’m imagining on dirt roads that probably if it rains really bad, you probably are not sure where you are.

Father Smith: Oh, it was less than a dirt road. It was often just a cow path. You’re right, when it rains, it became a problem. Some people thought it was a major transformation. I remember when I started telling my family and closest friends about deciding to enter the seminary, some were surprised, but most were not.

Megan Fleming: Why is that?

Father Smith: Because even when I was at Purdue and at MIT, a lot of what I was doing was involved with helping people, doing different volunteer work. At MIT, I was a dorm counselor. My dorm happened to be mostly freshmen. They would come to me with their problems, their struggles, and just talk to get advice. At Purdue, I was in a fraternity. Again, I was known as the philosopher or the person you go to with questions about life. We’d have all these long discussion with many different people.

Megan Fleming: See, I would’ve thought you were the treasurer.

Father Smith: I was also. Yeah, I was the treasurer first of the fraternity and then later the president of the fraternity. All the bonds were more on a deep human level rather than a scientific technical level.

Father Veneroso: Once you joined Maryknoll, I’m very intrigued by two incidents you mentioned earlier. Which prepared you most for life as a seminarian? Was it a man standing over you with a stopwatch, or was it artificial intelligence, or was it both?

Adam: Or was it the machine guns?

Father Veneroso: It was the machine guns, really.

Megan Fleming: Or maybe the troubles of the freshmen at the dorm.

Father Veneroso: Ah, yes.

Megan Fleming: The complaining I’m sure.

Father Smith: Wow.

Father Veneroso: I think the question is, given the silliness of it, the question is, because Father David’s path mirrors my own, the seminary years were the biggest jolt. Life in the missions were fine and before, but it’s almost like a grinding of gears to go through the seminary program.

Father Smith: I do recall the seminary experience was challenging in that it was unlike any experience I’d had before. It was somewhat a very regimented, lots of rules, though in my day I guess it was much less strict than the stories I hear from guys who preceded me, or even nowadays it seems like it’s gone back somewhat to be more strict. But it was not what I was accustomed to. I remember turning in one paper. It was the final paper for the semester.

It came back with a B+ on it. I went to the professor and said, “Well, what could I have done better?” I don’t remember exactly what he said, but it was something like, “Well, you didn’t say this, and this, and this.” I said, “But you didn’t tell us that we had to share those things or write about those things.” I said, “Coming from my scientific background, if the assignment is to do X, Y, Z, and you do X, Y, Z, you would get an A. You’re saying because I did X, Y, Z, but I didn’t do A, B, C, which was in your mind understood in this culture that that’s expected, that that’s why you gave me a B.” Actually, he relented and he said, “Oh, yeah, that’s true, I didn’t say that. I understand where you’re coming from,” and he gave me an A.

Father Veneroso: There you go.

Father Smith: I thought it was interesting that there are a lot of assumptions about the culture that I was not familiar with.

Father Veneroso: The United States culture?

Father Smith: The seminary culture.

Father Veneroso: Seminary culture.

Father Smith: Yes. We went to church every Sunday, but I wasn’t real involved in church. I was never altar boy. I didn’t know any priests personally. I didn’t know any nuns personally. I always felt that in a sense that to me affirmed my vocation. Even when I was making the decision to become a priest, I didn’t ask a lot of input from family and friends. I was talking to various priests, various religious orders, going to some retreats and things to consider it, but I wanted to make sure it was my decision and it wasn’t being pressured by family or friends to go one way or another. I always felt that it was a decision coming from my own discernment.

Father Veneroso: If we could go back to Africa in the discussion, many of our listeners, and I’d probably even include me, when we hear Africa, we think of the war. We think of refugees. We think of famine. I’m sure your experience was much deeper and richer than that. What did Africa teach you?

Father Smith: Africa taught me that life is all about human relationships. As I mentioned earlier, extreme poverty so poor that most Americans cannot even conceive of it. People lived in houses made of mud. The floor was dirt. The roof was grass. They lived off the land and were totally dependent on the land by taking a hand hoe to farm a few acres, and I mean two, three, four acres. They had to hope and pray that the rain would be enough that year, and many times it wasn’t. They would be so dependent on God’s providence that their faith in God was unshakable. It was amazing. It was a witness to me to see how strongly they believed. Their sense of community, the worst punishment in Africa is to be cast out of the community, to become a loner, whereas in Western culture, everybody wants to be independent. That’s not an African value. The strong bonds of community, relationships with one another, knowing that you can’t survive by yourself, that you have to depend on other people and depend on God, that was such a counter value to what was coming from in the American culture.

Megan Fleming: When you arrived to Africa, I’m just thinking your vast science mind, and very intelligent, when you got there, were you thinking, “How can I help these people when it comes to farming or medical?” How did you decide which projects to do first to help tackle their problems? I’m sure you had time to think when you were on your motorcycle.

Father Smith: Well, the problems are so vast that it’s very difficult and sometimes can be overwhelming for someone coming from Western culture to see the situation and to try to think, “What can I do to change everything, to make everything better?” I concluded after being there a while that the best way would be through education because when you education people, they can improve their own lives, they can improve their family’s lives, they can improve other’s lives, and they can pass that education on to their children, grandchildren, neighbors, etc.

Megan Fleming: You’re enabling them and giving them that power, that ability.

Father Smith: I spent a lot of time helping people obtain education either through helping them get into schools because even high school is not universally available there. They only provide through seventh grade. That’s what the government provides usually. Then they would have a test to see if someone would qualify. It was only about 5% would then get to go to high school. Of the 5% who went to high school, maybe only 5% went to university because there were only two or three universities in the entire country. Seminary was also another avenue for getting education, so many young men went to seminary. They’d need a letter of recommendation from the pastor. I probably helped dozens go to seminary. They got a good Christian education. Seminaries were often among the best educations available. Seminaries were high schools, and they would compete in national exams. They always were among the top scoring in the national exams. Some who went to the seminary then decided to go on to the major seminary to become priests. I know that four young men that I sent to seminary became priests and are still priests over there. I believe there are two women who were sisters who I sponsored to go to school and then joined different religious orders there.

Megan Fleming: How did you start the College of Health Sciences? Did that evolve from this need that you saw for education?

Father Smith: My understanding, that was one of the last works I did during my 27 years in Africa. The bishops were looking to do something about the healthcare situation. At that point, I believe there was one doctor per 30,000 people in Tanzania. There was only one medical school in the country. There was not a single Catholic medical school on the continent of Africa. With the urging of our regional superior, John Sivalon, he encouraged the bishops. Then our Father Peter Le Jacq was here in the United States doing fundraising. He also has a medical degree, so he has contacts at Cornell Medical School. He got a lot of funding and sponsorship from Cornell to start a medical school. While he was raising money here in the States, they needed someone on the ground back in Africa to actually start doing the work of creating a medical school. They got one professor of medicine, African professor of medicine, who became the first dean of the college. He and I arrived in Mwanza, which is right on Lake Victoria, at a big hospital, Catholic hospital. We were given one floor to the hospital to convert into a medical school. For about six months, we were a university of two people.

After six months, we finally got a secretary. He and I were working on various things. They wanted to model the education system on a computer-based learning system, so that was part of my expertise. I helped create the computer lab and set up the programs that the future students would be using, modeled after the system they use at Cornell Medical School. I was helping at that time design the library and the layout for the classrooms, even the layout for dormitories, things like that. The professor and I, I was basically doing everything that he didn’t want to do. He would be writing up notes on all these applications to the government to get approval to open a university, and I’d be typing them up, and formatting them, and going back and showing him. Finally, we submitted our application, and we got approval after another six months. Then we started with a class of 10. That was in our second year there.

The next year we took a class of 25. Nowadays I believe they’re always taking class of 50, but they’ve graduated several classes since I began there. Some of those very first students, of course when there’s only 10 students, you get to know all of them very well. I was very pleased, one of them recently came to New York, came to visit me. He was in this country because he is now one of the few ophthalmologists in Tanzania. He came to attend the conference of American ophthalmologists. That was nice to see that he has done so well and he’s helping so many people.

Megan Fleming: Right. Was it specifically ophthalmology, or was it general medical [inaudible]?

Father Smith: Our college at Bugando was the basic medical degree.

Megan Fleming: Okay.

Father Smith: Then several of them would go on to-

Megan Fleming: To specialties.

Father Smith: … To become specialists, so he went on to specialize.

Adam: This is really interesting. I’d like to know if the observation I have is pretty accurate. I know a lot of people might be saying to themselves, “This is a guy who was an AI major at MIT and goes to become a priest,” where most of the interviews we do with the other missioners, there’s some type of divinely inspired calling. But with you it almost seems that logic and reason just made sense because it sounds like to me, and I may be wrong, but it sounds like to me the model that has inspired you, your framework, has been going from chaos to order and going from, “Okay, this makes sense. Let’s do the math. Okay,” which ultimately is, if we go back to earlier in the discussion where you say you feel most close to God among the trees, and the water, and close to nature, which algorithmically is just math. It’s going to order. Maryknoll would be the path to that, so everything just made sense. Am I accurate in that?

Father Smith: Yes, I would say that’s a good description, though throughout my early life it was like I never had a faith crisis. It was always a good foundation.

Father Veneroso: Even after you joined Maryknoll?

Father Smith: I always had a good foundation, went to church. I went to public school. I didn’t go to Catholic school, but did go to CCD classes once a week. Went through the normal stages of receiving various sacraments, and basically believed the Catholic teachings. So, I felt comfortable in that. It’s sort of like the seed of vocation was growing very slowly, but it was there. Maybe not visible for a long time. I could feel an attraction, especially when I really started considering, “All right, what do I want to do with my life?” When I was at Purdue, my summer jobs for five summers, high school and beginning first couple years of college, I was a lifeguard because I was a swimmer, swimming team in high school.

Last two years of Purdue and first year at MIT for my summer job I went to a high tech company in California that recruited me to work there for the summer. It was an ideal job for someone who was studying computer science and artificial intelligence, so I had a good understanding of what that life could be like if I continued down this path. It was a marvelous job setting where you set your own hours, even days of work as long as you get the job done. Very, very high pay for a college student back then. It should’ve been ideal, but it just didn’t fulfill me. It left me thinking, “Do I really want to do this for the rest of my life? Isn’t there something more meaningful that I want to do with my life?” That fed the growing seed to think more and more about answering a call from God.

Adam: Did you finish your degree at MIT?

Father Smith: No, I did not. I decided that, “Okay, if I’m going off to be a missioner, I don’t think this degree is going to help me any.”

Adam: It’s not too often that you get the opportunity to talk with someone who went to MIT studying AI and they become a priest. What’s your opinion of the emerging technology in robotics and some of the fear around that or the emergence of AI and where it collides with spirituality and faith?

Father Smith: I’m not sure I can exactly answer your question, though I do recall from my experiences in the mid ’80s, I was ordained in 1985, I believe in 1986 or 1987 I brought the first laptop computer among the Maryknoll missioners to Africa. All my other confers, the priests and brother Maryknollers said, “Oh, that’s a stupid idea. What are you going to do with that in Africa? You don’t need that.” I said, “Well, we’ll see.” Literally within three or four years they all had computers, and they were all asking me how to use them. I have seen in Africa the whole issue of education. When I first got there, we had trouble getting a blackboard and chalk for the teachers. I would buy special paint that they would paint on a piece of plywood, and that would serve as the blackboard for the classrooms. Now they’re all studying computers. It has amazed me how fast the technological revolution has reached into even the villages of Africa.

When I first got there, I would sometimes drive my motorcycle 20, 30 miles off to a village expecting to have mass because I’d sent a written note with somebody weeks ahead of time, only to arrive and find nobody’s at the church. I’d drive around to look at the catechist, and he’d say, “Oh, we never got the note.” Nowadays they all have cell phones in every single village. Every single day I receive WhatsApp messages from my friends in Africa. Technology has certainly changed the world. But it’s interesting, for Africans it’s still all about the relationships, keeping connected.

Having a cell phone, that fit right into their culture because they’re always on the cell phone now. I still follow developments in AI. In a sense, I’m a little disappointed that it hasn’t advanced as quickly as early predictions were saying. I think we’re still a long way off from having a machine that truly thinks. Things we’re calling AI are very specialized programs right now. The machines aren’t thinking. They aren’t conscious. Yet I also am a big fan of science fiction, so I read stories or see movies where the theme is that the machine has become conscious. Once the machine becomes conscious, then the next question is, does the machine have a soul? How is mind related to soul? I think it’s an intriguing question. I certainly don’t have any answers. I believe that the Church will be continue to be challenged.

Early on when the internet was just starting to become popular, John Sivalon again sent me to Rome to find out what’s the Church going to do about using the internet for evangelization. I met with the people in Rome who were working on the Vatican website. At that point, they didn’t have a whole lot of plans, though they were and still are, I believe, one of the premier sites in terms of multilingual presentations for their website. They are thinking a lot about using the internet for reaching people. It would be interesting to think about how would you use AI for evangelization. I imagine other religions are thinking about the same thing.

Adam: That concern of exponential self-learning, its singularity though is the one that the people who are in the theological space are concerned about, that all of a sudden once it hits that point, self-learning goes exponential. Then all the questions come up.

Father Smith: Exactly, yeah, because at that point the worry is does the computer, the singularity, still believe that humans are relevant? If the computer far exceeds human intelligence and if it has the capability of continually improving itself, it would improve itself so fast that humans would become mere ants to it.

Father Veneroso: But then in at least the Catholic point of view, the cross, we’re looking at it as perfection and intelligence as being the goal. What about vulnerability? What about mortality? It’s in wrestling with our mortality that our humanness gets perfected. Will a machine contemplate its own mortality, or will it try to overcome it? In fact, many human beings, the way we were taught, a lot of the addictions and what not that human beings get into is precisely to avoid their mortality. When we face our mortality, that’s when these other things come out. That’ll be the crossroads, as it were, between human intelligence and artificial.

Father Smith: That’s true, and again, it is one of the themes in science fiction. There’s a very famous story, which became a Robin Williams movie, the Bicentennial Man, where he is a robot that becomes more and more human-like until he has to petition the court for the right to die.

Adam: Tesla or Harley? Tesla or Harley motorcycle, which would you prefer?

Father Smith: A Tesla.

Adam: Okay. When you were in Africa, what kind of bike did you ride?

Father Smith: Well, it was a trail bike of course because we were going through mud and sand. It was a Honda.

Megan Fleming: Well, thank you, Father Smith. We appreciate you making time.

Father Smith: Oh, thank you. I enjoyed talking to you.

Father Veneroso: You’ve been listening to the Maryknoll podcast Among the People. To learn more about the work of Maryknoll around the world, visit our website, maryknollsociety.org. Or if you’d like to subscribe to our English or Spanish magazines, visit maryknollmagazine.org. You know, we’d really like to hear what you have to say about this episode, so please leave your reviews, comments, or questions below. Feel free to share this podcast with friends or anyone you feel may be interested. This has been Maryknoll Father Joe Veneroso, along with co-host Megan Fleming for Among the People. Till next time.

Megan Fleming: The views and opinions expressed by those we interview in this podcast do not necessarily reflect those of the Maryknoll Fathers & Brothers and the hosts of Among the People. This podcast offers unique insights and personal stories of people from all walks of life as we explore unfamiliar perspectives and the unique experiences of mission from around the world.

by Adam Mitchell | Aug 2, 2019 | Podcast

Today we sit down with one of the most recognizable and respected Maryknoll missioners, Maryknoll Superior General Fr. Raymond Finch.

For those of you who are fans of Maryknoll, you know Fr. Finch from the weekly Journey of Faith reflection he sends you every Sunday.

Originally from Brooklyn, N.Y., Fr. Finch was inspired by one of Maryknoll’s first priests and fellow Brooklynites, Bishop Francis Xavier Ford, who was martyred in China in 1952. Fr. Finch was one of the first students to attend the school in Brooklyn named in honor of the martyr, Bishop Ford High School.

Journey with us to the highlands of Peru, where Fr. Finch worked with the indigenous Aymara community for over 20 years.

Fr. Finch reminds us that in mission we have to meet people where they are, not where we want or expect them to be.

by Adam Mitchell | Jun 28, 2019 | Podcast

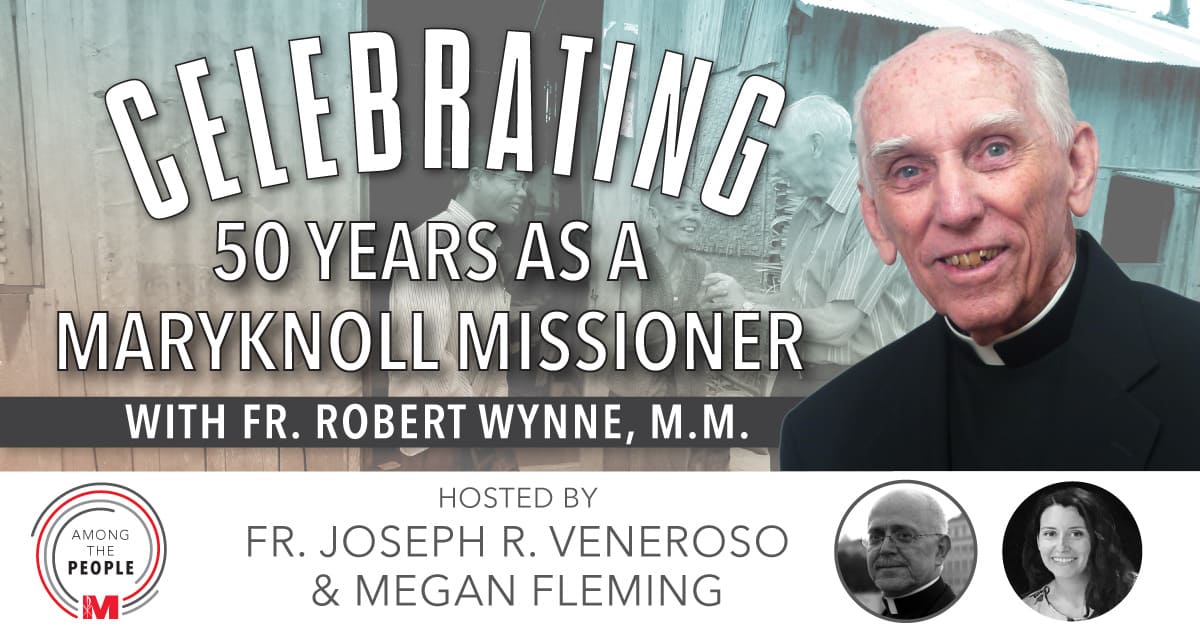

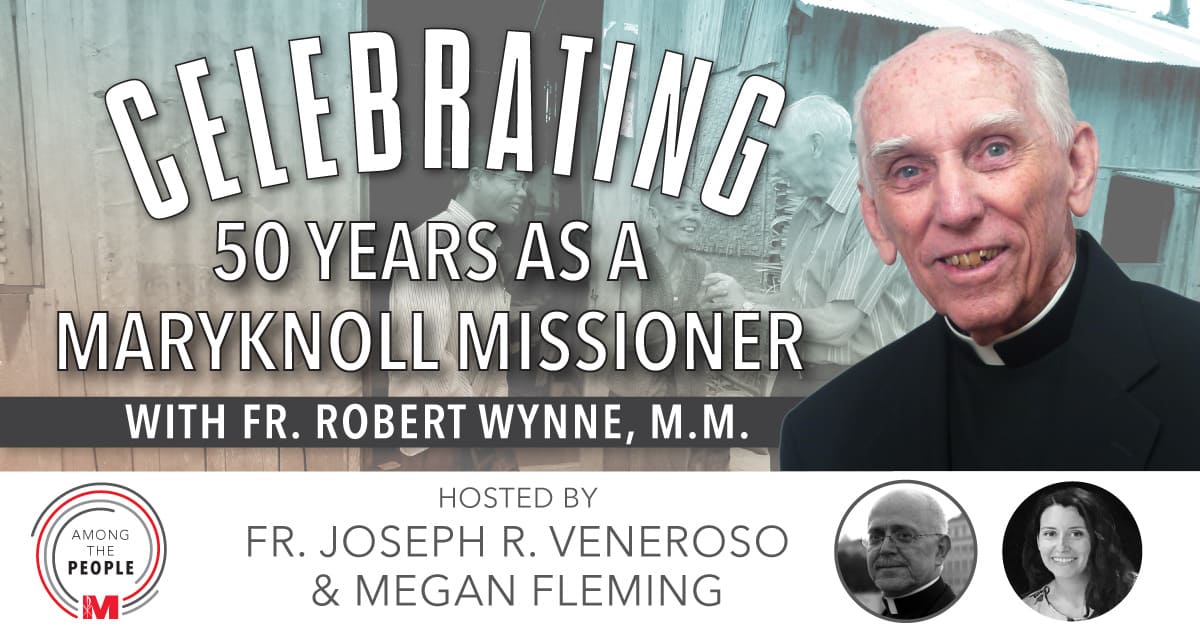

In this episode we sit down with Fr. Robert Wynne who celebrates his 50th Jubilee as a Maryknoll Missioner this year.

His 50-years of Mission work have included Hawaii as well as Cambodia, an active missionary country of which Fr. Wynne requested to join at the age of 68 in 2007.

Fr. Wynne share’s stories of his missionary work and the transformative qualities of the people he’s worked with during his career as a Maryknoll Missioner.

by Adam Mitchell | Jun 24, 2019 | Podcast

This is a special episode of Among The People, “A Story of Hope for South Sudan” from some of Maryknoll Missioners who have worked and are still active in Mission in the South Sudan with Fr. John Sivalon. This informative presentation goes through the history, challenges, and future hopes of the South Sudan.

by Adam Mitchell | Jun 14, 2019 | Podcast

Although Br. Ryan recently took his permanent oath to a life of service with the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers, he has already had a substantial amount of experience as a missioner. With life changing experiences situations in Jamaica and Bolivia, Br. Ryan learned early in his mission experience that ‘being present’ for those most in need has helped not only those he serves, but also himself during the most difficult times in mission.

About Br. Ryan Thibert, M.M.

Brother Ryan Thibert acknowledges that he felt an attraction to religious life growing up in a strong Catholic family. He sought direction from his parish priest, who knew Maryknoll and thought it might be a good fit for his mission-oriented parishioner.

Brother Ryan Thibert is a native of Ontario, Canada. He was born a minute after his twin brother, Aaron, and four years after their sister, Jennifer. He credits his parents, Larry and Rox-Ann Thibert, for his love of service because of their unconditional love.

Having met Society members like Brother Robert Butsch has helped Ryan. He says it is by witnessing how passionate they are about their work and seeing how the Holy Spirit seem to work through them inspired him. He became aware that he can use his own educational background and artistic talent to help people be the best they can be.

“I realize that it is in living for others through Christ where I feel truly happy and at peace.” ~ Brother Ryan Thibert, M.M.

A short-term mission trip to Jamaica with three other prospective Maryknoll candidates sealed his decision. Working at the Blessed Sacrament Orphanage in Montego Bay, and remembering the Franciscan brother who had come to console his family when his grandfather died made him realize that being present, giving life to those who need love is the essence of the brother’s vocation. That is what he felt the Holy Spirit was calling him to do. So in 2011, he decided to join the Maryknoll Brothers’ formation program.

He completed his undergraduate degree in art at St. Xavier University in Chicago all the while deepening his spirituality through prayer and theological studies.

He underwent his overseas training program in Cochabamba, Bolivia, where young missioners are immersed in language study and life in another culture as well as various pastoral works as they continue to discern their call to cross-cultural mission. He will return to Latin America where he has been assigned to work in mission.

by Adam Mitchell | May 24, 2019 | Podcast

Fr. John Barth, M.M. Life long mission work with refugees

Fr. John Bath has been a Maryknoll Missioner for 28 years and has extensive mission experience working with refugees in Cambodia and South Sudan.

In this episode, you will hear how Fr. Barth built a successful program in Cambodia to train the blind in massage therapy. This program was so successful that it is still active in both Cambodia and now Peru.

Seventeen years later, Fr. Barth is now working with the South Sudanese refugees in Uganda, delivering food and supplies to villages and schools.

Join us as Fr. Barth shares his journey from an unfulfilling government job in Albany, NY to his Calling to make the world a better place through his ministry.